News

News

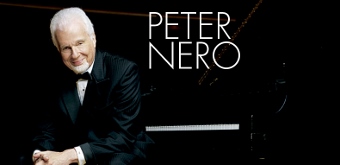

Peter Nero and the Philly Pops open 34th Season

by Peter Dobrin

No one does variety hour quite like Peter Nero. In fact, in the old show-business sense of it, nearly no one but Nero practices the form at all anymore. And when Nero moves on at the end of this season from his 34 years as chief of the Philly Pops, the concept may disappear altogether.

Nero himself may not consider what he does to be of the variety-hour variety, but consider what tapped and shuffled across the stage Friday night: the concertmaster from Buffalo playing a tango tune from a recent film; a song-and-dance duo with a tribute to Fred and Ginger; direct from Spain, the dark and handsome classical guitarist you may have already seen on YouTube; a free-wheeling Richard Rodger symphonic tribute. And more.

In case you haven’t already guessed it, the variety weighed in at considerably more than an hour, at 2 ½. Of course, there was Nero himself, presiding over the whole evening from the keyboard with occasional quips about politics and a pianistic facility that straddles what could have been in lesser hands a tasteless overlapping of classical and jazz. He has the gift of making it sound like these two worlds were conceived as two halves waiting to discover each other.

Nero takes three more programs this season, and then he’s gone. He’s been picked up by a savvy New York agent who has booked him for concerts in other cities. The Pops’ new leaders have not said which conductor is taking over next season, though it can’t be another Nero. It’s a small talent pool, these pianist-composer-pops conductors with major recording careers. Until recently, it included just one other member: Marvin Hamlisch, who had been, until his death in August, first choice as Nero’s successor. Nero dedicated part of this weekend’s Philly Pops program to Hamlisch, playing a medley from A Chorus Line.

The bulk of the program, though, was taken by Joan Hess and Kirby Ward, who personified the kind of smooth professionalism that Nero has consistently imported in his guest choices. Singing and dancing to songs from the 1930s, they took over a small portion of the Verizon Hall stage in front of the ensemble. If you were constantly afraid someone was going to put a Capezio through a cello, you could take particular pleasure in the small-framed Kirby, an elegant presence who managed to make the famous scene from “Singing in the Rain” his own rather than aping Gene Kelly.

The orchestra went silent and the house dark when a spotlight shone on Pablo Sáinz Villegas, a classical guitarist who created an impressive reserve of tranquility in Koyunbaba, a plaintive and sometime microtonal evocation of a mystical Turkish shepherd by contemporary Italian guitarist/composer Carlo Domeniconi.

This was about as far from 1930s song and dance routines as you could get. Or Khachaturian’s “Sabre Dance.” Or Count Basie. On paper, the juxtapositions look absurd. But they work. And it’s safe to say that when the task at hand is morphing a Tchaikovsky 5/4 waltz with Richard Rodgers, there’s only one maestro for the job, and your chances to hear him are quickly drawing to a close.